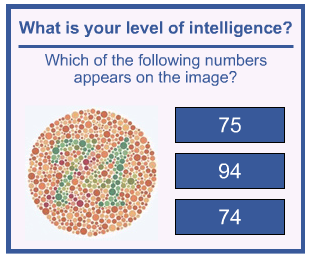

Like 10% of the population, I can never fly a fighter jet in the army. This is what I was told, when the optician informed me that I was colour-blind. What I wasn’t told was that I’d be rubbish at Alien Vs Predator online. However in 1999, I discovered that I couldn’t aim, since the red retina in the green predator vision was practically invisible to me. I didn’t realise it then, but it was my first encounter with accessibility in games.

A good player experience relies on enabling the gamer to feel like a valued participant, and be able to contribute fully within the game. For an increasing minority of players this requires taking their disabilities into consideration, which has often proved to be difficult, since game studios are under constant pressures such as tight budgets and imminent deadlines. This has led to the unwitting sacrifice of a large potential player base, with up to in some form. This article covers the mistakes that studios are making and successes with enabling gamers to play despite disabilities. A future article will discuss how current trends in gaming, such as 3D and motion control, are making accessibility one of the key areas to watch in the next year.

protip: don't insult your users

What is accessibility?

Accessibility involves taking disabled gamers’ needs into account when designing a game, and ensuring that they will be able to enjoy the game in the same way that other players can, without being suffering an unnecessary disadvantage due to their disabilities.

The field of accessibility has risen to prominence on the internet, where legal guidelines have been created to ensure that websites are accessible by disabled users. This includes techniques such as using alt tags to describe images, and properly marking navigation elements, so that blind people using a ‘screen reader’ can have the page read to them, or using closed captioning to allow deaf people to follow videos.

Accessibility requires an awareness of the range of disabilities out there, and defensively designing to account for them, through special options or design choices. The advantage of taking accessibility into consideration when building a game is obvious – your game can reach more players, and your disabled players will be happier. If they can play your game, and not the competition, it’s an easy sell!

Games and Accessibility – Successes

Accessibility has become a major consideration when designing for the internet, yet has had a less enthusiastic reception within games. Since games are an entertainment medium, effectively legislating to make accessibility a legal requirement is complicated. So, despite the existence of a few games built specifically for disabled players, gamers wanting to play high profile games have traditionally found it difficult.

Problems can range from annoying, such as using red and green to distinguish between friend and foe, which is impossible for colour blind users, to game breaking, such as audio-impaired users not being able to hear necessary audio cues. Obvious and ‘easy’ requirements like configurable controls are often left out of high profile games, making the game impossible for players with one hand to control.

Recently there have been some advances for accessibility in games. Both Doom 3 and Half Life 2 both featured closed captioning, which allowed audio impaired users to follow the action, and most modern high-budget games, such as Arkham Asylum, give subtitle options for the cut scenes, although these often lack information on who is speaking, or subtitles for sound effects. However the majority of games still put deaf gamers at a disadvantage by forcing the player to rely on audio cues. This was obvious in Price of Persia: Sands of Time, which required the player to follow the sound of running water to successfully navigate a puzzle room, an impossible task for players who couldn’t hear. Too often it has fallen upon the modding scene to offer these gamers the complete experience.

Audio only games are important for blind players, and a few have emerged. These are no longer restricted to text-adventure games being read out by a text-to-speech program, but have branched out into innovative new directions such as Nintendo’s Soundvoyager, a collection of mini-games with no visuals, including one where the player must dodge traffic driving the wrong way down a high-way. The scene for audio-only games is on the rise, although it may well always remain a niche genre, and unlikely to attract hardcore gamers away from Call of Duty.

A screenshot of a sound-only game

Some disabilities cause players to find controllers difficult to use, restricting them to playing ‘one switch’ games, with only a single button. Canabalt on the PC and iPhone is a successful game which only requires a single button to play, and ‘one button games’ has proved to be a popular theme at game jam events. Countering the trend in gaming of ever-more buttons, the restrictions placed upon game designers by a one-switch game forces innovative thinking and new directions.

Popcap’s Peggle included a ‘colour-blind mode’, which imposed icons on top of the coloured pegs, allowing colour blind players to distinguish between them. This solution was simple, unobtrusive and yet made it possible for colour-blind users to enjoy the game fully, where other colour matching games have proved impossible to play. The most common form of colour blindness is the inability to distinguish the contrast between red and green, which unfortunately are common choices to denote friends or enemies within games.

But by far the game which has taken accessibility most seriously is Second Life, where the game’s creative nature has lead to the introduction of many features to cater for disabled gamers, and the open source client has allowed teams to make huge leaps in accessibility. One group of Second Life users are working on developing a virtual guide-dog, which will aid navigation and read signs to allow blind gamers to play. Other initiatives within Second Life include an accessible island featuring easily readable, high contrast signs, easily navigable doorways and wheelchair ramps for disabled avatars, as well as a virtual nightclub where disabled players can meet, and exchange tips or support for one another. It’s interesting to note in the freeform world of Second Life that many disabled users choose avatars that represent their disability, and still consider this an important part of their identity.

It’s obvious that despite these efforts, accessibility has a long way to go in allowing all players to enjoy gaming fully. In a future post, I will be looking at the challenges, and oppurtunities, that have arisen with this year’s high profile console releases.

Very interesting read, and a very important subject!

There are various projects in this area. For example, the aptly named

http://www.game-accessibility.com/

Also, there’s a wii game in development for blind kids, aiming to improve their balance:

http://www.gambas-games.com/?page=home&lang=en